Building Democracy - The Labour Party

The foundation of Dáil Éireann and Britain’s opposition to any element of independence resulted in the War of Independence, which eventually led to the signing of the Treaty in December 1921. The Treaty between Ireland and Britain established an Irish Free State, with dominion status within the British empire. The Sinn Féin party split over the terms of the Treaty, which was passed by Dáil Éireann. As an election was held in June 1922 the prospect of Civil War loomed.

Labour contested the June 1922 election, despite incidents of intimidation from elements of Sinn Féin. The result was remarkable, with 17 of Labour’s 18 candidates being elected, many of them topping the poll. While Sinn Féin was consumed with its own internal strife over the terms of the Treaty, it was clear that a substantial section of the Irish population wanted politics to focus on economic progress and social justice.

Labour accepted the democratic mandate that the people had given to the Treaty and Tom Johnson became the leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party in Dáil Éireann. Anti-Treaty republicans boycotted the Dáil so Labour effectively became the parliamentary opposition to the Cumann na nGaedheal government. Under Johnson, Labour argued strongly for its own agenda of employment, pensions and welfare. It also opposed the reactionary public order laws the government introduced in the wake of the Civil War.

In these early days of the state, democracy was fragile. Labour’s commitment to peaceful, democratic politics was crucial in ensuring that Ireland developed into a stable parliamentary democracy. Labour was also vital in securing the stability of politics by encouraging the majority of Anti-Treaty republicans, now organised under the Fianna Fáil banner, to accept the legitimacy of the state and enter the Dáil in 1927.

This was a selfless act by Labour. Fianna Fáil was better organised, better funded and had shamelessly adopted many of Labour’s social and economic policies as their own. In facilitating Fianna Fáil’s entry into constitutional politics Labour was assisting an opponent that threatened its own electoral base. However, Johnson and his colleagues put country before party and played a crucial role in securing parliamentary democracy.

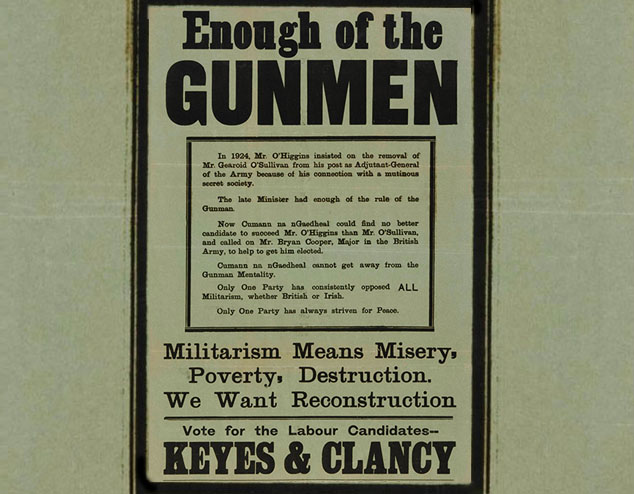

By 1932 popular disillusionment with Cumann na nGaedheal and the powerful organisational ability of Fianna Fáil saw a change in government. Labour, under TJ O’Connell who had replaced Johnson as leader after he lost his seat in September 1927, had battled the increasingly authoritarian and right-wing policies of Cumann na n Gaedheal and the Party supported the election of Fianna Fáil as a minority government. The Party secured commitments on housing, welfare and job creation in exchange for its support.

Bill Norton now took over the leadership of the Party, a position he would hold until 1960. Labour struggled during the 1930s to gain electoral support for its policies, no matter how progressive, as the two civil war parties Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael (Cumann na nGaedheal had merged with two other parties to form this new right-of-centre formation) dominated politics.

Its constructive role in the Dáil and Seanad continued however, and the public again turned to the Party in significant numbers in the 1943 election when Labour challenged the Fianna Fáil government over its economic and social policies adopted during the war years. In 1948, after 16 years in office, Fianna Fáil’s grip on power was finally broken and Labour prepared to enter its first coalition government. Despite that achievement all was not well within the labour movement.

Larkin had returned from the USA in the 1920s, but was estranged from the Labour Party. William O’Brien, then a leading figure in the ITGWU, was particularly opposed to Larkin and these tensions affected both the trade union movement and the Labour Party. When Larkin was re-admitted to the Labour Party and contested the 1943 election O’Brien left the Party, the ITGWU disaffiliated from Labour and a breakaway National Labour Party was formed.